A Teacher’s Wisdom

It is really easy to reduce relational teaching into simple soundbites. Build a bridge. Only connect. Maintain the students’ trust. Be stable and steady. Communicate clearly. Be positive. Hope. Believe. Be human.

Yet teachers know it’s not that simple because relationships exist in the interplay between teacher and student. They are human at their core and while they can be measured, they are nuanced. This is why Reach Academics workshops focus on teacher-driven examples of relational teaching through realistic case studies and role plays.

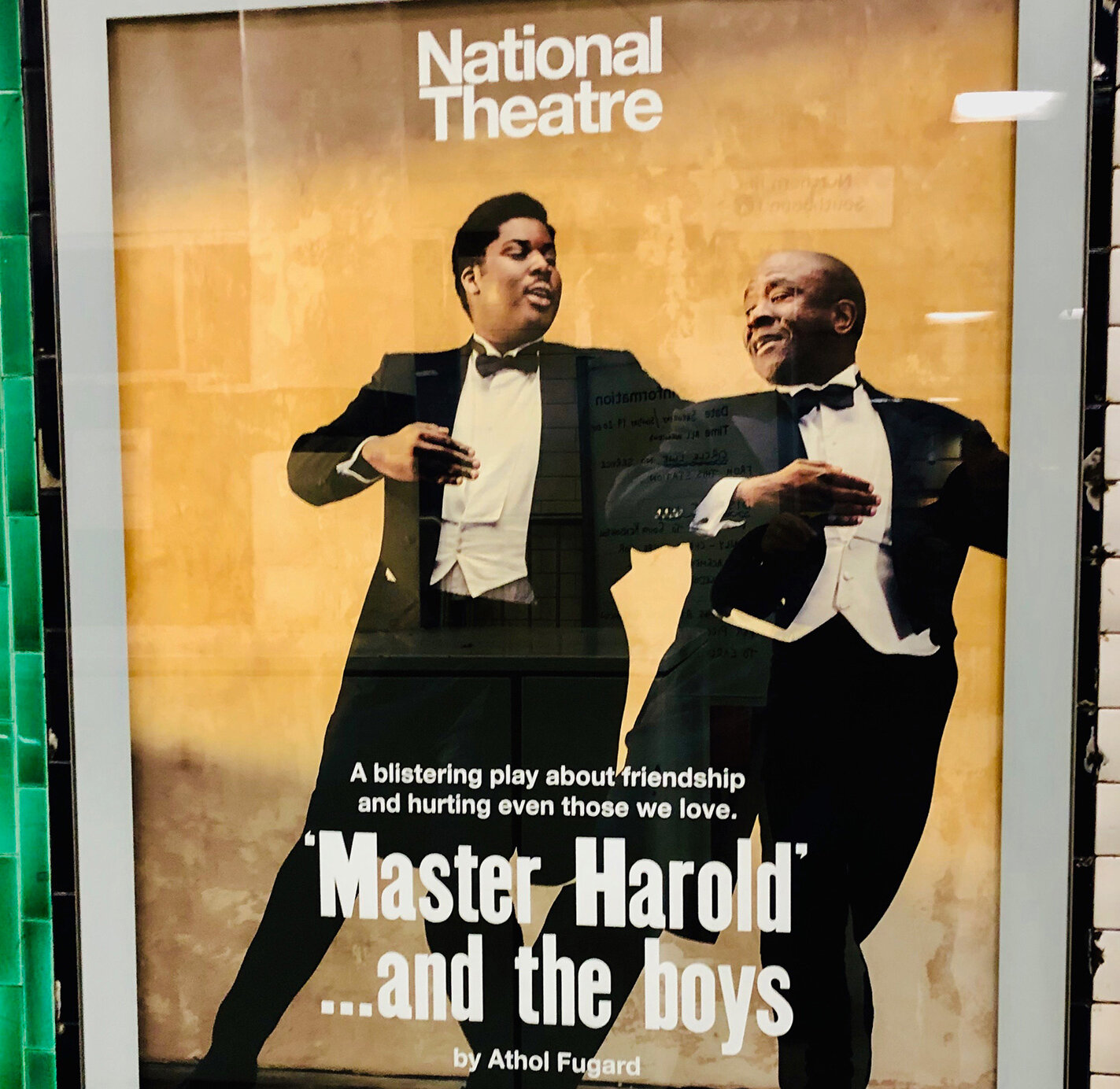

I wasn’t expecting to face a 100-minute role play a few nights ago. Yet there I was, in my seat at London’s National Theatre, watching Athol Fugard’s “Master Harold…and the Boys” and learning about relational teaching through Sam’s character.

Sam, the black servant, is the intellectual superior to Master Harold (“Hally”), the white prep school student half his age. Sam possesses wisdom and Hally has the book-smarts. If not for the racist politics of Apartheid pressing down on 1950’s Port Elizabeth, South Africa, we’d have no problems guessing which character is better positioned to succeed in life.

Throughout the play, Sam shares his wisdom with Hally on a level he can understand. He challenges Hally’s simplistic view of the world, one where he who possesses the most knowledge wins the game of life.

To Sam, learning is an escape to freedom. We get the strong sense that if Sam were afforded the educational opportunities Hally received, he would be a success in the eyes of society.

Sam also gets to the emotional side of his student. He knows Hally. He is deeply dialed in to Hally’s anxieties about school and his shame about his father. He remembers Hally’s struggles from childhood. He comes up with strategies to help guide Hally away from his negativity and toward a broader view of life. In this way, Sam conveys hope, which is an essential trait of a relational teacher.

I began this blog chapter by stating that relational teaching is not simple because the classroom is a microcosm of the messiness of life. The students we teach are unpredictable in their youth. Teaching requires patience. So when Hally spits in Sam’s face, the audience gasps, wondering what Sam’s response to this repugnant and racist abuse of power will be.

The response is the ultimate definition of self-restraint. The power of a teacher is measured not only in their course mastery but also in how they present themselves in relation to their students – in good and bad times. Sam’s dignity transcends the entire play’s resolution. And Hally is left to wallow in the residue of his own shame. We understand that he will remember that dark moment, long after Sam has passed on into the light, leaving that lesson behind for all who choose to learn it.

Based on the standing ovation this play received, it is clear that Sam’s relational lessons on restraint, hope, and love continue to resonate in 2019 like they did at its premiere in 1982.